Famous battles in the Vietnam War included Khe Sanh, Pleiku, Hamburger Hill and Ia Drang Valley. The biggest and most important battle of all was the Tet Offensive in 1968, with a large battle in Vietnamese imperial capital of Hue. Many regards the North-Vietnam-launched Tet Offensive as the "turning point" of the war. Even though the North Vietnamese were ultimately defeated they scored a decisive psychological victory—enough of one to force the U.S. to make getting out of the war their top priority.

The battle at Ap Bac in January 1963 has been called "the turning point of the early stages of the war" because it showed the Viet Cong were intent on winning the war and the South Vietnamese army was weak and more concerned about saving its ass than keeping Diem in power and fighting. At Ap Bac, for the first time, the Viet Cong fought at battalion strength and won a decisive victory against Vietnamese troops supported by American helicopters, armored vehicles, and artillery. Two Viet Cong soldiers received North Vietnam’s highest military-exploit medal for winning this battle. One was the commander of the Communist forces. The other was Pham Xuan An (See Spies), who devised the winning strategy.

In 1966, 1967 and 1968 there were a number of battles in the area of the DMZ. During 1966 there were eighteen major operations, the most successful of these being Operation White Wing (Masher). During this operation, the 1st Cavalry Division, Korean units, and ARVN forces cleared the northern half of Binh Dinh Province on the central coast. In the process they decimated a division, later designated the North Vietnamese 3d Division. The U.S. 3d Marine Division was moved into the area of the two northern provinces and in concert with South Vietnamese Army and other Marine Corps units, conducted Operation Hastings against enemy infiltrators across the DMZ. The largest sweep of 1966 took place northwest of Saigon in Operation Attleboro, involving 22,000 American and South Vietnamese troops pitted against the VC 9th Division and a NVA regiment. The Allies defeated the enemy and, in what became a frequent occurrence, forced him back to his havens in Cambodia or Laos.

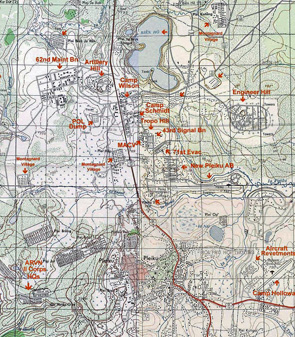

In February 1965, the North Vietnamese attacked a U.S. military instillation in Pleiku, killing eight and wounding more than a 100. A few days later at Qui Nhon 23 Americans were killed and 21 were wounded. In response U.S. President Lyndon Johnson launched Operation Rolling Thunder and ordered bombing of North Vietnamese barracks and staging areas. The attacks, Johnson said, were "carefully limited military areas" and was "appropriate and fitting" because "we seek no wider war." A couple weeks later 3,500 U.S. Marines arrived at Danang. A few months after that the United States scored its first major victory at Chu Lai, where more than 5,000 U.S. troops defeated an estimated 2,000 Viet Kong.

According to History.com: February 10, 1965: "Viet Cong guerrillas blow up the U.S. barracks at Qui Nhon, 75 miles east of Pleiku on the central coast, with a 100-pound explosive charge under the building. A total of 23 U.S. personnel was killed, as well as two Viet Cong. In response to the attack, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered a retaliatory air strike operation on North Vietnam called Flaming Dart II. This was the second in a series of retaliations launched because of communist attacks on U.S. installations in South Vietnam. Just 48 hours before, the Viet Cong struck Camp Holloway and the adjacent Pleiku airfield in the Central Highlands. This attack killed eight U.S. servicemen, wounded 109, and destroyed or damaged 20 aircraft. [Source: History.com **]

"With his advisors advocating a strong response, President Johnson gave the order to launch Operation Flaming Dart, retaliatory air raids on a barracks and staging areas at Dong Hoi, a guerrilla training camp 40 miles north of the 17th parallel in North Vietnam. Johnson hoped that quick and effective retaliation would persuade the North Vietnamese to cease their attacks in South Vietnam. Unfortunately, Operation Flaming Dart did not have the desired effect. The attack on Qui Nhon was only the latest in a series of communist attacks on U.S. installations, and Flaming Dart II had very little effect. **

After the Pleiku attack, McGeorge Bundy, one of Lyndon Johnson’s top advisors, wrote a report that included a recommendation that the U.S. develop a "sustained reprisal policy" using air and naval forces against North Vietnam. According to Bundy, the situation in South Vietnam was: " deteriorating, and without new U.S. action, defeat appears inevitable-probably not in a matter of weeks or perhaps even months, but within the next year or so. There is still time to turn it around, but not much." [Source: eHistory archive, OSU Department of History]

According to eHistory; " just prior to the VC attack on Qui Nhon, General Westmoreland offered his appraisal of the war. He recalled that in the past he had considered requesting American combat troops to provide for close-in security of the U. S. bases in Vietnam. This course of action had been rejected for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was that the presence of American forces might cause the South Vietnamese to lose interest and relax. The general was now of the opinion that the attack on Pleiku marked a new phase of the war. With direct Communist attacks on American personnel and facilities, MACV could no longer ignore the question of protecting these troops. Westmoreland believed that this would require at least a division declaring: "These are numbers of a new order of magnitude, but we must face the stark fact that the war has escalated." [Source: eHistory archive, OSU Department of History]

In "Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War," David Coleman and Marc Selverstone wrote: "Bundy’s presence in Vietnam at the time of the Communist raids on Camp Holloway and Pleiku in early February—which resulted in the death of nine Americans—provided additional justification for the more engaged policy the administration had been preparing. Within days of the Pleiku/Holloway attacks, as well as the subsequent assault on Qui Nhon, LBJ signed off on a program of sustained bombing of North Vietnam that, except for a handful of pauses, would last for the remainder of his presidency. While senior military and civilian officials differed on what they regarded as the benefits of this program—code-named Operation Rolling Thunder—all of them hoped that the bombing, which began on 2 March 1965, would have a salutary effect on the North Vietnamese leadership, leading Hanoi to end its support of the insurgency in South Vietnam. [Source: Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War, David Coleman, Associate Professor and Chair of the Presidential Recordings Program, Miller Center of Public Affairs; Marc Selverstone, Assistant Director for Presidential Studies and Associate Professor with the Presidential Recordings Program, Miller Center of Public Affairs <>]

While the attacks on Pleiku and Qui Nhon led the administration to escalate its air war against the North, they also highlighted the vulnerability of the bases that American planes would be using for the bombing campaign. In an effort to provide greater security for these installations, Johnson sanctioned the dispatch of two Marine battalions to Danang in early March. The troops arrived on 8 March, though Johnson endorsed the deployment prior to the first strikes themselves. Like other major decisions he made during the escalatory process, it was not one Johnson came to without a great deal of anxiety. As he expressed to longtime confidant Senator Richard Russell (D-Georgia), LBJ understood the symbolism of "sending the Marines" and their likely impact on the combat role the United States was coming to play, both in reality and in the minds of the American public.

The bombing, however, was failing to move Hanoi or the Viet Cong in any significant way. By mid-March, therefore, Johnson began to consider additional proposals for expanding the American combat presence in South Vietnam. By 1 April, he had agreed to augment the 8 March deployment with two more Marine battalions; he also changed their role from that of static base security to active defense, and soon allowed preparatory work to go forward on plans for stationing many more troops in Vietnam. In an effort to achieve consensus about security requirements for those troops, key personnel undertook a review in Honolulu on 20 April. Out of that process came Johnson’s decision to expand the number of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam to eighty-two thousand.

According to eHistory archive: "Following the Qui Nhon attack, on 11 February the Joints Chiefs of Staff forwarded to the Secretary of Defense a program of reprisal actions to be taken against Communist provocations. The chiefs observed that the retaliatory air raids against North Vietnam had not achieved the intended effect. They recommended in its place a "sustained pressure" campaign to include continuing air strikes against selected targets in North Vietnam, naval bombardment, covert operations, intelligence patrols and cross-border operations in Laos, and the landing of American troops in South Vietnam. On 13 February, President Johnson approved a "limited and measured" air campaign against North Vietnam, which took the code name ROLLING THUNDER. The ROLLING THUNDER campaign was delayed until 2 March because of a combination of bad weather and the instability of the South Vietnamese political situation. [Source: eHistory archive, OSU Department of History]

In mid-February, the South Vietnamese were in the midst of another power struggle. Confronted with both a deteriorating political and military situation, General Westmoreland directed his deputy, Lieutenant General John L. Throck-morton, USA, to determine what American ground forces were needed for base security. After completing his survey, Throckmorton recommended the deployment of a three-battalion Marine expeditionary brigade to Da Nang because of the vital importance of the base for any air campaign against the north and "the questionable capability of the Vietnamese to protect the base." General Westmoreland several years later recalled: "While sharing Throckmorton's sense of urgency, I nevertheless hoped to keep the number of U.S. ground troops to a minimum and recommended instead landing only two battalions and holding the third aboard ship off shore. "